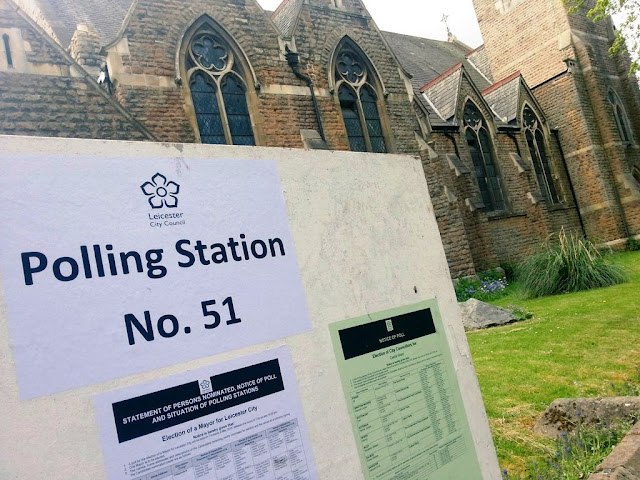

This article on the prospects for a Progressive Alliance of the non-Conservative parties at the next general election appears in the new issue of Liberator. You can download it (issue 414) from the magazine's website.

It was meant to be a review of Duncan Brack's pamphlet 1997 Then and Now: The Progressive Alliance That Was and the One That Could Be, but turned into the sort of review you get in the TLS or London Review of Books.

By that I mean that it's one where the reviewer is less interested in the book in front of them than setting out their own ideas. Still, a lot of what I say is in line with the views in the pamphlet,

Embed from Getty Images

Four into one won't go

With its thick concrete walls, the Progressive Alliance control bunker lies deep beneath the soil of… We’d better keep its location a secret, but I can tell you what you will find there. The room is dominated by a table whose top carries a constituency map of Britain and across which WAAFs with victory roll hairdos slide little figures representing voters.

“Less than six hundred votes needed for Labour to gain High Peak,” barks a voice from the gantry that overlooks the room. “Withdraw the Liberal Democrat candidate.” A WAAF pushes some orange voters into the red group.” “Labour gain High Peak, sir.”

And that, if you believe what you read on social media, is all opposition parties need do to win the next general election. Labour, the Liberal Democrats and the Greens, together perhaps with Plaid Cymru and some smaller parties, should reach agreement to field only one ‘Progressive’ candidate between them in every constituency in England and Wales.

Some early models of this Progressive Alliance (PA) also included the SNP, but such is its dominance of the Scottish scene, holding 48 of the 59 Westminster seats there, that it’s hard to see what it has to gain from joining such an arrangement. Besides, Scottish elections now see Unionist voters operating an alliance of their own, happy to fall in behind whichever party has the best chance of defeating the Nationalists in each constituency, and the SNP may well calculate that keeping a Conservative government in office at Westminster improves its chances of winning majority support for Scottish independence.

Would a PA defeat a reviving Conservative Party? Could it even win if the Conservatives were ahead in the polls? Supporters of the idea point out that the Tories never win 50 per cent of the popular vote, so that in many constituencies they win despite polling less than the combined votes of the parties in the proposed alliance. All we have to do is put those votes together behind a single candidate, the reasoning goes, and the Conservatives may never form a government again.

Problems problems

There would be many practical problems in establishing such an alliance. The first is that Labour’s constitution has always been taken to rule out any electoral pacts with other parties, though some way round this must have been found at Tatton in the 1997 general election, where both Labour and the Liberal Democrats stood down in favour of the Independent Martin Bell.

A second problem is that if Labour agreed to join an alliance, there would have to be agreement between it and all the other parties over who would fight which seats. Liberal Democrats of my generation have memories – perhaps “flashbacks” is a better word – of the endless hours consumed in meetings between the Liberal Party and the SDP to decide which party would represent the Alliance where – hours that would have been more profitably spent on campaigning, watching Dallas or almost anything else. Even if agreement could be reached in time for the next election, it would be at a similar opportunity cost.

Then there is the problem of what policy platform the PA would stand on – there would surely have to be some sort of agreement on policy to give voters an idea of what they are voting for, particularly if we are asking them to vote for a party they don’t usually support. One idea that you read on social media can be ruled out: a one-line manifesto pledging to introduce proportional representation for general elections. If we fought on that while the Conservatives talked about the economy, defence and education – no matter how stupid we thought what they had to say on those issues was – the Conservatives would win and deserve to win. We would certainly want to secure some movement from Labour on proportional representation and constitutional reform in general, but if we are exhausted after the seat negotiations it would be easier to agree some form of statement promising to undo the worst of the damage the Conservatives have cause on poverty, the environment and the economy.

We should also have to overcome the fact that a PA would threaten to hang around our necks the gaffes and objectionable views of every Labour and Green candidate around our necks. At the very least, Lib Dem candidates fighting the Tories in our target seats would have to cope with being called “the Labour/Lib Dem candidate” on all their leaflets, and even if the other PA candidates conducted themselves blamelessly, we should still have to cope with all the worst policies of their national parties. The Greens, for instance, want to leave NATO, but not while the war in Ukraine is going on. It’s hard to see that rallying disappointed Conservatives to the PA flag.

Would it work?

When all that had been accomplished, one question would remain to be answered: would a Progressive Alliance be worth all this trouble? Parties cannot deliver their voters en bloc to another party because those votes do not belong to them: they belong to the individual voters. Some specially commissioned opinion polls give encouragement to the idea, but the trouble with them is that they do not seek information like conventional polls (“How would you vote if there was a general election tomorrow”) but rather ask people to forecast what they would in a hypothetical situation at some unspecified point in the future (“If there were an electoral pact between X, Y and Z parties at the next election and this resulted in you having only a Y candidate to vote for, how would you vote?”

And the trouble with that, as psychologists will tell you, is that we are not very good at forecasting our own actions. We are actually better at forecasting other people’s, because we take into account a wider range of factors when we look at them. We wonder how our neighbours will be influenced by the election campaign, but are, wrongly, confident that we are far too secure in our own beliefs for it to affect us.

And even a PA could be agreed, it would contain subtle dangers for the Liberal Democrats. As Simon Titley asked in Liberator 346:

‘Progressive’. What does it mean? The only discernible meaning is ‘not conservative’ or ‘not reactionary’, but those are negative definitions. … The ‘p’ word is a lazy word, so give it up. It will force you to say what you really mean, and that’s a good thing.

It may be that being against the Tories will be enough at the next general election, but in the long run the ideology-light Liberal Democrats need something more to found a party on.

1997 and all that

But maybe we can learn something from 1997, when a limited sort of PA operated between Labour and the Liberal Democrats and helped bring about the rout of the Conservatives. We Lib Dems saw our vote decline by one per cent, yet made a net gain of 28 seats.

Duncan Brack has written a pamphlet for Compass, 1997 Then and Now: The Progressive Alliance That Was and the One That Could Be, looking at the lessons to be drawn from that experience. It reminds us that that the cooperation between the two parties in 1997 was the result of much work, both public and private.

The public work took place in the talks between Labour’s future foreign secretary Robin Cook and the former SDP leader Robert Maclennan talks. Between them they agreed a package of constitutional reforms, which included incorporation of the European Convention on Human Rights into UK law, freedom of information legislation, devolution to Scotland and Wales (and elections by proportional representation to their parliaments), an elected authority for London, the removal of hereditary peers from the House of Lords, proportional representation for the European elections and a referendum on voting reform for Westminster elections that gave a choice between the existing first-past-the-post system and a proportional alternative.

As Duncan Brack says, much of this was already Liberal Democrat policy – some of it was watered down to be accepted as part of the package – but the agreement did break new ground for Labour. And most of it was implemented by the Blair government. The exceptions were the referendum on a proportional voting system for Westminster elections and the total removal from hereditary peers from the Lords, where a deal brokered by the former Commons speaker Lord Weatherill saw 92 of them allowed to remain.

When Paddy met Tony

Meanwhile, the private work took place in talks between Tony Blair and Paddy Ashdown. These looked at electoral cooperation and the possibility of a wider policy agreement than that reached by Cook and Maclennan.

Tony Blair, says Duncan Brack, was keen on the idea of the two parties backing a single candidate in a limited number of seats, and accepted that in some the candidate would be a Liberal Democrat. Remembering the hours lost in negotiations with the SDP, Ashdown vetoed this idea saying it would appear “a grubby plan designed to gain power and votes for ourselves, instead of one based round principles and what was best for the country”.

This line was forced on Ashdown, who had earlier floated the idea of closer cooperation between the parties, by the Liberal Democrats’ polling. This showed clearly that the soft Conservative voters the party was targeting would be happy for it to enter government with Labour in the event of a hung parliament but were hostile to the idea that it should campaign with Labour for that outcome.

So the parties turned to covert cooperation, concentrating on the same issues and using the same language. They avoided attacks on each other, shared information on which seats they were targeting and jointly gave the Daily Mirror a list of 22 seats where Labour voters should back the Liberal Democrats.

In the event, Liberal Democrat supporters proved to be more prepared to vote tactically than Labour supporters. The Labour vote went up in some Liberal Democrat targets, but such was the fall in Conservative support that we still won some of them. I don’t know if they were official targets, but Labour also came from third place to win two seats we had rather fancied winning ourselves: St Albans and Hastings & Rye.

Building trust and relationships

Duncan Brack concludes from this history that parties should not try to negotiate a national pact. Instead, he says:

Any level of cooperation between non-Conservative parties will need to be more fluid and organic than it was in 1997, built from the bottom up as well as the top down – hence the Compass focus on local groups and building trust and relationships over the long term.

This could feature a wide range of approaches – including, possibly, local electoral agreements but, more importantly, cooperation in local campaigns and policy discussions, building a common understanding and appreciation of parties’ positions and potential solutions to the challenges the UK faces in the mid-2020s.

And I am happy to support his conclusion, which takes us a long way from that Progressive Alliance Control Bunker:

Whatever the form a progressive alliance takes, whether it’s an electoral pact or encouragement for tactical voting, the parties that form it need to give an indication to the electorate of what will be the result if they vote for it: a positive agenda of reform, not merely the negative case for getting rid of the Tories.